What makes a work

of art Sacred? The subject matter, of course, but ancient tradition goes

much further than that. Some artworks, it was said, have miraculous

properties. Gabriele Paleotti, 16th

century archbishop of Bologna, defined what those special properties

were in 1582:

An image is

called sacred if it enters in to contact with the body or with the face

or with other parts of our Lord or one if his saints, where, just by

means of that contact, the figure of the body or the part of the body

that was touched is printed there.

An image is

called holy that would be made by a holy person, like those made by St

Luke or painted by other saints.

An image is

called holy because it was made in a miraculous manner, that is, not by

the hand of man but invisibly, by the work of God, or by other similar

means.

An image is

called holy when God has performed manifest sounds and miracles in that

image, as are seen at times with the face radiant, at times with tears

spilling from the eyes, or drops of blood, or they make some movement as

if they were alive: also God, through them, has, in an instant, healed

the sick, restored vision to the blind and liberated others from various

dangers.

To the modern

sceptic this is nonsensical, but nevertheless, the tradition is a

fascinating one. In this study I’ll be looking at a range of artworks

that match the archbishop’s criteria, and asking the question, could

some strange truth be lurking behind these beliefs?

I will divide the archbishop's final holy definition into two

parts; images that produce sound or make movements, and images that work

miracles.

1. Miraculous by touch

The two best known examples of this are the Turin Shroud and the Veil of Veronica. We'll look at these two relics here.

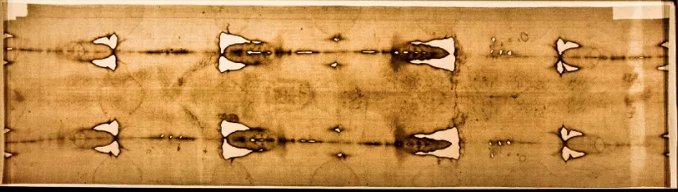

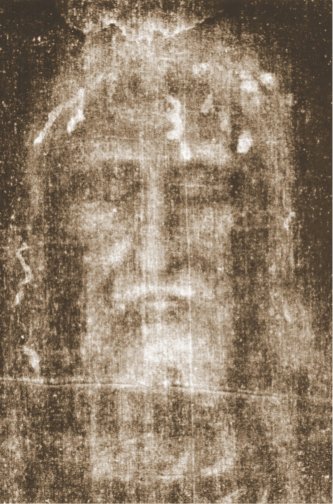

The Turin Shroud

Opinions still rage over

the Shroud of Turin, said to be the burial shroud of Jesus. There is no

history of it before the mid fourteenth century, and some were

suspicious of it even then.

Recent scientific analysis

has cast much doubt on the claimed provenance. Radiocarbon dating dates

the shroud to c1260, though some still argue that this is due to later

contamination. Perhaps the most decisive denial of the legend is the

material used to make it, which is woven in a manner far advanced from

that used in biblical times.

There is still, however, a

question about the shroud that cannot be answered – how the image

appeared (or was put) on the shroud. It remains a much-venerated relic.

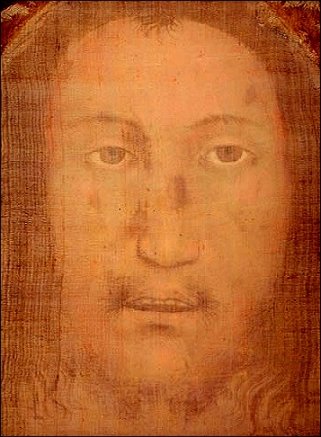

Statue of Veronica and the Veil, St Peter's Rome

Via Crucis Station 6

The story of the Veil of Veronica comes from various confusing medieval

legends. It was said that a woman named Veronica wiped the sweating face

of Jesus as he carried the cross, and a miraculous image appeared on the

veil. It occurred at the sixth station of the Via Dolorosa in Jerusalem

– see my photograph above. The legend continues; Veronica then took the

veil to Rome and used it to cure Emperor Tiberius.

Was there really someone called Veronica? It is suggested that

the name was formed from the Latin word ‘vera’ (truth) and the Greek

word ‘eikon’ (image).

Its presence in St Peter’s Rome is shrouded in mystery. A

‘Veronica chapel’ was in place in the early 8th century, though the

first mention was in 1101. By the third century the veil was annually

paraded through Rome.

Now was it destroyed during the sack of Rome in 1527? Was it

taken elsewhere – there are a number of relics claiming to be the

original in various places. Or is it still in St Peters? A relic there,

said to be the veil, is displayed once a year in Lent, though there is

no discernible image.

Below is one of the relics from elsewhere, the

one with the best image; The Manoppello Image, now in a church in

Manoppello in Italy.

On to page 2