|

|

|

|

|

|

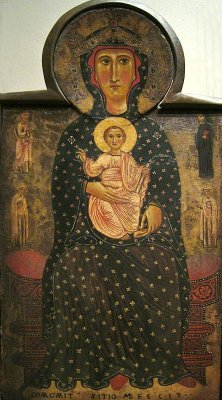

So why a special study of this rather obscure painting? In the spring and summer of 2011 the National Gallery in London put on an exhibition called Devotion by Design: Italian altarpieces before 1500. Being rather taken with such things my wife and I went twice. Among the many wonderful altarpieces on display was this one. On both visits, this painting, the oldest in the National Gallery, attracted something of a crowd. O.K., crowd is a slight exaggeration, but people did find it difficult to tear themselves away from it. Why? Because they were trying to work out what the various narrative scenes were, and they couldn't. (At this point in the exhibition the paintings were set out as if in an Italian church, and too much detail in the form of captions would have spoilt the effect.) We were scratching our heads too. There was only one thing for it - to do some research. First port of call - the really excellent National Gallery website. This did tell us what the scenes were, so we were somewhat the wiser, but in some cases not much. This is how they were described: Saint John the Evangelist in a cauldron of boiling oil; Saint John the Evangelist resuscitating a woman called Drusiana; The Nativity with the Annunciation to the Shepherds; Saint Benedict rolling in brambles to overcome the temptation; Saint Nicholas' warning to the pilgrims to throw deadly oil given to them by the devil into the sea; Saint Catherine beheaded and her body carried to Mount Sinai by angels; Saint Nicholas miraculously saving three innocent men from being decapitated; and Saint Margaret in prison swallowed by a dragon and escaping unhurt. Well, we had already worked out the Nativity and John the Evangelist 'in oleo', but what about the others? And what were those creatures flying round the Madonna? And what was she sitting on? The picture The National Gallery exhibition showed the painting standing at the back of a simulated altar. This was correct, though it can't be described as an altarpiece - it is too small, and the wrong shape. Technically it is a dossal, a panel (or, more often, a decorative cloth) that formed a backing or retable for an altar. It was painted sometime in the 1260s. It is sometimes linked with a painting described by Vasari in the church of Santa Margherita in Arezzo, but this is an error repeated on a number of websites. It was collected in 1845 from a church in the Arezzo area and purchased by the National Gallery in 1857*. The fact that St John the Evangelist and St Nicholas both have two scenes suggest possible dedications for this unknown church; on the other hand, its small size could mean it is a retable from a side chapel dedicated to one of these saints. * The Italian Schools Before 1400: Martin Davis (N.G./Yale U.P.) The choice of scenes on the panel is puzzling. Apart from the Nativity, it shows scenes from the lives of saints, but it's an odd mixture. Margarito generally avoids the better known incidents in the lives of the chosen saints, and there seems to be no coherent message: we have miracles, and examples of piety and sacrifice, but all rather random. The artist Very little is known of Margarito (or Margaritone), though Vasari writes about him in his Lives of the Artists. (Click here for Vasari's full text.) He is described both by Vasari and modern scholars as an artist rather behind the times for the thirteenth century - he worked from around 1250 -1290. He was still painting in the 'Greek style', and was wary of the new kids on the block such as Cimabue, (c1240 - 1302) Duccio (c1255 -1318), and later, Giotto, (1266 -1377) who, in Margarito's later years, were developing very different approaches. |

|

|

|

Nevertheless his work was much

prized in his day. Vasari's listing of his paintings makes one realise, sadly, just how

much work from this period has been lost. Apart from the London panel

there still exist a number of panels of St Francis, and this Virgin and

Child enthroned with four Saints, now in the National Gallery in

Washington.

Sources |

|

The

Madonna |

St

Margaret |