|

The Naked Jesus |

|

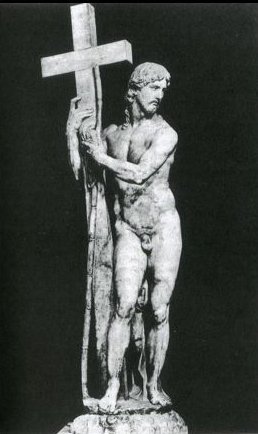

| Another photograph of the final version of The Risen Christ from Santa Maria sopra Minerva, this time with the 'breech clout' removed. The image on the right is a copy by Taddeo Landini, carved in the 1580s and now in Santo Spirito in Florence. |

|

|

|

|

| A couple

of things to note. At some point the Michelangelo had been emasculated,

or to be more correct, penectomied. (Compare with the first version.)

Landini's version of fifty years later is decently swathed. What had

happened in the years since Michelangelo carved the Risen Christ? Michelangelo and nudity. Leo Steinberg discusses the theological correctness of the nudity of The Risen Christ in his book The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion. I will try and summarise his two key points here. 1) Like the prelapsarian Adam and Eve, Christ was without sin. As Steinberg puts it, 'is it not the whole merit of Christ, the New Adam, to have regained for man his prelapsarian condition? How then could he who restores human nature to sinlessness be shamed by the sexual factor in his humanity?' In other words, it is the covering up that is shameful, not the exposure. 2. Christ was God made human. The nudity of Christ was a clear demonstration of his humanity.

Note: I have more so say on Steinberg and the nude Christ in my

discussion of the Christ Child and the nativity here.

Michelangelo's models were the classical sculptures continually

being dug up around Rome. |

|

| So

what happened? As the sixteenth century progressed, the Italian mindset changed. As early as the last decades of the fifteenth the apocalyptic preaching of Savonarola cast doubt on the liberal humanism of the Renaissance, with its freedom of thought and adoption of pagan images and classical models in art. Pope Alexander's lifestyle in Rome did nothing to counteract Savonarola's views. In 1517 Luther's 95 theses were published, though whether he actually nailed them to a door is a matter of some debate. Ten years later came the watershed event of the sack of Rome. Elsewhere in Italy, republics or benign autocracies were being replaced by controlling despots. Papal self-indulgence is a contentious issue, then and now. Vast amounts of money were spent on building and beautifying St Peter's, and creating works of art that are life-enhancing wonders of the world. The thought of not having the Sistine Chapel is unbearable. And yet, as Luther pointed out, much of the money was raised by the dubious practice of the sale of indulgences. It can be argued that these things were created to the glory of God, but personal and often ostentatious self-indulgence is a different matter. Leo X's interest in and respect for classical (i.e. pagan) learning is understandable, even commendable, but did he really need a pet elephant? The pendulum swung, and by mid-century free thought was under strict control by the Inquisition, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, and the edicts of the Council of Trent. These would not have appealed to Michelangelo: ...every superstition shall be removed ... all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust... there be nothing seen that is disorderly, or that is unbecomingly or confusedly arranged, nothing that is profane, nothing indecorous, seeing that holiness becometh the house of God. And that these things may be the more faithfully observed, the holy Synod ordains, that no one be allowed to place, or cause to be placed, any unusual image, in any place, or church, howsoever exempted, except that image have been approved of by the bishop ...

And so the great cover-up started. Perhaps the best known example

is Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine chapel, painted over

with drapery in 1564 by the artist Daniele da Volterra on Papal orders. |

|

|

|

|